Greening History Teaching and

Civics Curriculum

Greening history teaching means including the rest of Nature and the environment in the study of history. History has, historically, focused on human relationships, especially conflicts. Traditional history teaching portrays the history of the Earth in terms of environmentally devastating wars and the conquest of Nature ... calling this progress.

The Earth existed for billions of

years before "life" appeared, and for many more millions of years

before our human ancestors evolved. But our teaching of history seems

always to start with early civilizations — as though nothing of import

or interest occurred on this planet before the invention of cities. Why

is that? And how can we change it? Through greening history teaching.

The goal of environmental history is to deepen our understanding of how humans have been affected by their natural environment through time, and conversely ... how they have affected that environment and with what results.

— Donald Worster, Environmental Historian

What is environmental history? How do we "green" the teaching of history? Eminent history professor, J. Donald Hughes, explains that it is "a kind of history that seeks understanding of human beings as they have lived, worked and thought in relationship to the rest of Nature through the changes brought by time."

Hughes, among other scholars, is concerned about the far-reaching alterations of land, sea and air caused by our species, noting that "the changes humans have made in the environment have in turn affected our societies and our histories."

There are three main themes of environmental history:

- the influence of environmental factors on human history

- the environmental changes caused by human actions and the many ways in which human-caused changes in the environment rebound and affect the course of change in human societies

- the history of human thought about the environment and the ways in which patterns of human attitudes have motivated actions that affect the environment

Social scientists ... have traditionally

portrayed the history of the Earth in terms of the rise and fall of

great civilizations, wars, and specific human achievements. They

essentially ignored environmental contexts that often triggered and

mediated these events. Based on the last decade of research, we are now

beginning to understand the complex ways in which humans have affected

and have been affected by environmental change.

— Rik Leemans and Robert Costanza

History teachers can contribute to transformative sustainability education and greening history teaching through helping their students

- see the deep and wide-ranging connections between human affairs and the rest of Nature and the natural environment

- gain an understanding of ecofeminism and a sense of "herstory" as well as history, through (eco)feminist readings and examining the role of women in creating the human world (definitely with Professor Carolyn Merchant's study in The Death of Nature; Elaine Morgan's 1972 The Descent of Woman would also be an interesting starting point, despite her controversial theories)

- look at history from multiple perspectives to uncover the meaning of photographer

Aaron Siskind's quote, "We look at the world and see what we have learned to believe is

there." (Gavin Menzies' 1421: The Year China Discovered America is a fascinating example of "historical" writing from a different — and controversial — perspective; including the perspectives of indigenous peoples is vital)

- see how many ways history overlaps and integrates with other subject areas and topics

- the history of indigenous peoples

- the history of science

- the history of ecological thought and environmental change

- the history of climate change, and the history of food and agriculture (every student should learn cautionary tales, such as the story of the 1930s Dust Bowl in America)

- the history of medicine (and its link to issues of population)

- the history of technology (the main way our species interacts with the rest of Nature)

- the history of commercialism and consumerism (watch the Story of Stuff)

- the history of civilizations that disappeared and the history of a culture that has become completely unsustainable, etc.)

- the history of religion and its relation with the natural world

- the history of conflict and war

With our new powers we banished some historical constraints on health and population, food production, energy use, and consumption generally. Few who know anything about life with these constraints regret their passing. But in banishing them we invited other constraints in the form of the planet's capacity to absorb wastes, by-products, and impacts of our actions.

— John McNeill, in Something New Under the Sun: An Environmental History of the Twentieth Century World

- gain a sense of their miraculous evolution from stardust to 21st century Homo sapiens living in a planet's biosphere that is threatened by climate disruption

- learn and discuss answers to the "big questions" of environmental history

- Who are we? What are we?

- What is our common history as a species?

- Who were our ancestors? How did they regard us?

- What causes massive human migrations?

- How did large-scale agriculture develop?

- Why did cities begin? How did civilizations come about?

- Which cultures have proven sustainable, and why? Which have disappeared, and why?

- What have been the benefits and the drawbacks of the Industrial Revolution?

- Why are we in the Sixth Mass Extinction?

- learn how to think critically to respond to compelling history questions

- In what ways can ecology trump imperial power, and how have mosquitoes shaped human destiny (John McNeill, 2000)?

- What were the "biological allies" that helped Europeans invade, conquer, settle and control large swaths of non-European territory (Alfred Crosby)?

- How does the proverb "When elephants fight, the grass gets trampled" apply to Africa's history? How does Africa's history affect us?

- What was life like before we were deliberately turned from citizens into consumers following World War II?

- How has our relationship with the rest of Nature changed over the course of our species' history?

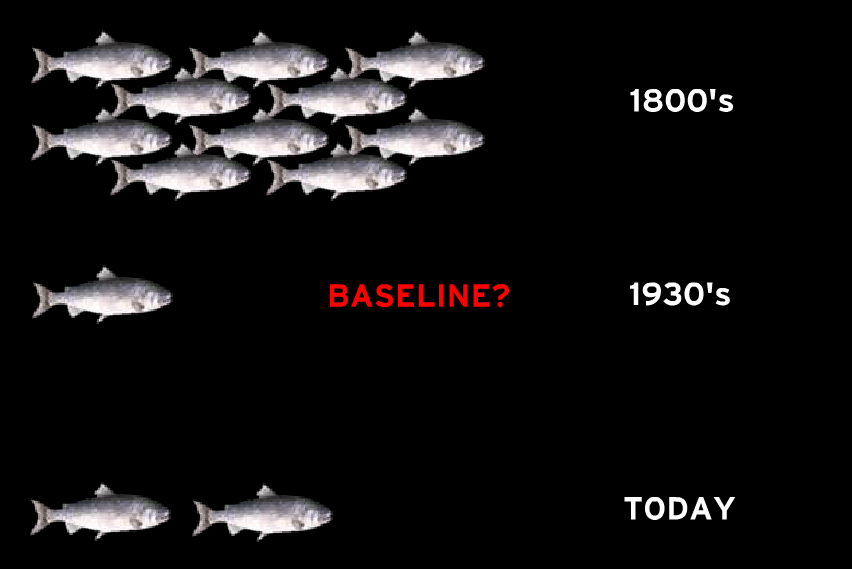

- learn about "shifting baselines" or cultural / inter-generational amnesia (According to shiftingbaselines.org, "A baseline is a reference point from the past — how things used to be. Shifting baselines are the chronic, slow, hard-to-notice changes in things, such as the disappearance of birds and frogs in the countryside. If we allow these reference points to shift, we lose track of our standards, and eventually accept the degraded state as being 'natural.'")

- read The Engineering of Consent by Edward Bernays (or watch The Century of the Self), to grasp the concept of sociological shifting baselines and manipulation of the masses

- start thinking in terms of both micro and macro history (the history of this plant in this place as well as the history of that industry in that environment; studying a small place broadly and deeply, as a model for the bigger world)

- see the intersections and interactions between history (time) and geography (place)

- value storytelling and oral history (perhaps by creating their own oral history through bioregional mapping, "ecological self" banners, or personal timelines), thereby integrating learning about time (history) with learning about space (geography)

- explore the evolution of the human relationship with the rest of Nature

- explain the impacts of the Black Death and the Inquisition in changing the European view of humanity's relationship with the rest of Nature

- learn about the history of their country's major food crops and diet

- gain a deep sense of their place in the world (its history, their family's history in it, their own history)

- start to think like ancestors

SUSTAINABILITY

by Peter D. Carter

Grandfather,

tell me again

of the things you have seen.

Of the forests,

trees towering like highrises,

wide as highways.

Tell me again

of bison herds,

hooves that shook the ground

like a million jackhammers,

hours before you could see them.

Tell me again —

flocks of pigeons

that darkened the sun

like a hundred bomber squadrons

as they flew by.

Oh, tell me again

of the rivers

so full of fish you could walk over them

like a silver-plated bridge.

Grandfather,

I can't wait to grow up

so I will be able to see them all ...

with you.

Academic achievement is important, but the sole function of a school shouldn't be to turn out good test-takers. Schools should also be developing the skills of civic participation, and students should be exploring their communities and helping to make them better, healthier places to live. If it's only academics, you diminish the virtue and potential that school can achieve.

— David Sobel

Civics teachers can contribute to transformative sustainability education by helping their students

- keep the significance of the natural environment in mind throughout the course

- learn the principles and processes of sustainable development as a framework for personal, family, local, regional, provincial, and national discussion, planning, consensus building, and decision-making

- note not only their environmental rights (to clean air and water, for example) but also their environmental responsibilities as citizens

- explore some big questions in civics (Do non-human animals have rights? Does the Earth have rights? What are our responsibilities to the rest of Nature? What role does sacrifice (for future generations) have in citizen responsibilities as well as in ecology? In other words, how much does our biology as animals impact our lives as a social species, as human beings?)

- learn about and emulate eco-heroes

- study the concept of "political will" and how it is created in their own country — and by whom; understand the role of civil society and especially environmental NGOs (nongovernmental organizations) in political participation

- show the connections between environmental degradation / environmental racism, social equity issues / human rights, and resource depletion / war and armed conflict

- discuss who climate change is affecting first (the world's most vulnerable — and least responsible in terms of greenhouse gas emissions — populations) and who will be impacted over time (everyone on Earth)

- learn about food security in their region, and how they can contribute to it; study the concept of food "sovereignty"

- explore their nation's relationship with the natural environment (How has the rest of Nature impacted the nation's identity and "psyche"? Why do people live where they live? How have the nation's artistic expressions and other cultural activities been affected by the natural world?)

- question how certain inventions have affected their nation (eg, the automobile, telephone technologies)

- look at a timeline of environmental history and see what, if any, events they have personal connections to (eg, pollution control measures have perhaps positively impacted their health)

- explore the possibility that chronological "progress" is a false paradigm

- participate in a local civics issue (eg, writing letters to elected officials, attending a city council meeting, setting up an information table in a shopping centre)

- examine how civilizations have collapsed due to social and environmental abuses and apply these lessons to present times

- learn about the role of empathy in creating successful civilizations (watch Jeremy Rifkin's lecture, The Empathic Civilization, remembering what Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel said: "One may contemplate history from the point of view of happiness. But actually history is not the soil of happiness. The periods of happiness are blank pages in it.")

Empathy is the keystone to civilization…. To empathize is to civilize. It's the invisible hand of civilization. Our historians have been looking up the wrong tree, for a long time. Because our historians chronicle pathology — all the bad events, the genocides, the blowbacks, the exploitation, the wars, the conquests, the redress of grievances, the power struggles.

Why? Because those are unique, they're novel, they're extraordinary. They're not what we see every day, so they become newsworthy. But then when you chronicle all of history this way, as a pathology, we have a pretty grim picture of the human race. It's embedded in our mind. It depresses our psyche. If that's who we were over history, we would never have made it to today. We would have perished a long time ago.

— Jeremy Rifkin on The Empathic Civilization

Resources for Greening History and Civics

- The Great Story (the life's work of Connie Barlow and Michael Dowd, who introduce the miracle of life to people of all ages; students can create their own Universe Story using beads, for example)

- The Ocean Conservancy's Pristine, an enlightening slide show about shifting baselines

- Gaylord Nelson and Earth Day: The Making of the Modern Environmental Movement

- The writings of Murray Bookchin, founder of social ecology, a critical social theory that purports that the oppression of workers, people of colour, women, children and the rest of Nature is all the same and all comes from the same worldview

- Anything by Howard Zinn, who urged us to learn the history of the oppressed, from the perspective of the oppressed (and not just the victors)

- The Death of Nature: Women, Ecology, and the Scientific Revolution, by Carolyn Merchant (the seminal book on eco-feminism, and groundbreaking work on environmental history)

- Anything by Father Thomas Berry, especially The Universe Story (with Brian Swimme)

- A New Green History of the World: The Environment and the Collapse of Great Civilizations, by Clive Ponting

- Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900-1900, by Alfred W. Crosby

- Something New Under the Sun: An Environmental History of the Twentieth Century World, by J. R. McNeill

- Mosquito Empires: Ecology and War in the Greater Caribbean, 1620-1914, by J. R. McNeill

- An Environmental History of the World: Humankind's Changing Role in the Community of Life, by J. Donald Hughes

- What Is Environmental History?, a student textbook by J. Donald Hughes

- The Atlas of U.S. and Canadian Environmental History, edited by Char Miller

- The Sixth Extinction, by Niles Eldredge

- Silent Spring, by Rachel Carson

- Collapse, by Jared Diamond

- Guns, Germs and Steel, by Jared Diamond

- A Short History of Progress, by Ronald Wright

- Indian Givers: How the Indians of the Americas Transformed the World, by Jack Weatherford (a fascinating look at crucial contributions made by indigenous North Americans to government, democratic institutions, modern medicine, agriculture, architecture, and ecology)

- The works of George Perkins Marsh, a 19th century American ambassador-turned-conservationist who studied the history of the places where he was stationed (he discovered that almost all civilizations had practically destroyed their environments)

- Endangered Planet: The Environmental Cost of Growth, a look at the environmental movement of the 20th century, in the video series People's Century

If we are to understand where we are and where we are headed, it helps

to know where we have come from.

— Lester Brown, founder and president

of Earth Policy Institute and former president of Worldwatch Institute

It's important to view history not as dead and gone, but as something we participate in every day and continue to shape.

— Ken Sandler, Co-Chair of US Environmental Protection Agency's Green Building Workgroup

The main thing history can teach us is that human actions have consequences and that certain choices, once made, cannot be undone. They foreclose the possibility of making other choices and thus they determine future events.

— Gerda Lerner, Professor emerita of history, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Those who cannot learn from history are doomed to repeat it.

— George Santayana

Human history becomes more and more a race between education and catastrophe.

— H. G. Wells

History provides a society with its backdrop — its mythology, world views, and cultural assumptions (which are blared at us but invisible to us) — but EuroAmerican history, and the teaching of EuroAmerican history, tend to omit Nature and the environment, again disconnecting humans from the natural world. What is real to students is what is given narrative on blackboards and computer screens, in textbooks, lessons and tests. Students learn by inference that Nature is irrelevant — it is given no story because it has no place in the history curriculum.

History is often still taught as a litany of who's, what's, where's, and especially when's: dates of wars and battles and their winners and losers. Little time is given to opening students' eyes to the how's and why's of humankind's history, and even less time is given to the history of human impacts on their ecosystems and interactions with the Earth.

Greening history teaching can be transformative if we become aware of the hidden curriculum: traditional history teaching shows students that war is acceptable and human disconnection from Nature is normal. There is nothing about sustainability in history as it is taught, which teaches that the way we've done things is the way to do things. It is vital to base environmental history on ethics, moving from an emphasis on war and empire building to an exploration of peace and community building.

J. Donald Hughes reminds teachers to place humans within the community of life, not to look at humans and the environment as separate entities.

Finally, because "history" usually tells the exploits of wealthy EuroAmerican men (in our culture, at least), it is also important to include the teaching of "ourstory," which includes the stories of families and communities and their connections with the Earth (and the earth) and the rest of Nature.

Return from Greening History

to Integration as a Sustainability Teaching Tool

Visit Environmental History:

A Transformative Tool in Sustainability Education

Go to GreenHeart Education Homepage